It’s the eve of the long-awaited announcement from Apple about its e-reading / kindle-killing / publisher saving / book destroying tablet computer.

It’s the eve of the long-awaited announcement from Apple about its e-reading / kindle-killing / publisher saving / book destroying tablet computer.

In the Twittersphere, the feed has been lighting up with people reporting from Digital Book World in New York, and everyone is looking to the future, trying to discern the horizon line somewhere in the distance.

Over here, where we’re still cutting down trees and binding sheaves of paper together, I’m struggling with the last piece of copy for my Book Construction Blueprint that I’ve been working on.

It’s the chapter on “E-Books.” Here’s my problem: like all truly new and breakthrough technologies, the e-books of today are rudimentary and obviously transitional.

The model for almost all e-books is a printed book original, or an imagined printed book original. What I mean is that we have ported the conventions of bookmaking from the world of paper and board into the digital realm simply for our own convenience. They are signposts, markers that help us orient in this new world.

How Is an E-Book a Book?

Reading through various instructions about formatting e-books, parts of e-books, helpful hints about e-books, it’s pretty obvious that the authors are making it up as they go along. All the instructions boil down to one question:

How slavishly does the e-book have to follow the physical conventions of the print book?

But, just for fun, off the top of my head, how is an e-book most definitely not in any way a “book” at all?

- E-books have no pages. Pages, the two sides of the leaves of paper that make up the book, are intrinsic to printed books. Although e-books imitate “pages” it’s just for our convenience. There is no reason an entire novel in e-book form couldn’t be written on one “page” or on thousands of bits of displayed text within a programmed environment.

- E-books also have no spreads. Although it seems like I’m repeating myself, this is the heart of the book. When the sheaves of papyrus or linen or wood pulp paper are bound they naturally create two (or more) side-by-side pages, or a spread. What makes a book is the binding, so the spread is really the basic unit of the book, not the page.

- Every word in an e-book is equidistant from every other word in the e-book. Any location in the e-book can be connected instantly to any other location in the text through hyperlinks.

- The text of an e-book is searchable and subject to computer analysis. Just by entering a search term and hitting the Return key, you can highlight thousands of occurrences of the term throughout the entire text. Instantly.

- There is no need in an e-book for text to be linear. An e-book, like almost all text-delivery systems, presents text in orderly rows of type on discrete, sequential pages, but this has nothing to do with the form of the e-book and everything to do with habits and expectations. We are used to reading text that way, so designers have created a model of the book on the screen. With just a little more work they could and do create models that have no debt to the book, where text is free-form, or timed to appear at intervals, or integrated with other media, or reading in circles if they bloody well want it to.

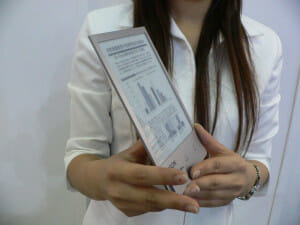

- The form, size and typography of the e-book are adjusted by the devices on which they are presented. I have hanging over my desk a page from a religious text printed in Paris in 1495 by a printer named Ulrich Gering, and I have no doubt that Ulrich himself set up this page and printed it on his pull-lever press. With many e-books, the user can change the typeface, the typesize and other attributes. The e-reader itself will create the format for the pages and how they are displayed.

The Pull of History Cannot Outlast The Push of New Technology Forever

Eventually, of course, popular e-books will break free of their need to imitate print books. But the force of habit and convention is strong. When the first graders are given “kinder-kindles” to learn reading, the transition will be pretty complete. Text has become data. Until then we’ll use the printed book as our guide, because it’s what we know.

E-books will continue to have “covers” although it’s impossible to say what’s being covered. Indexing will die off, since in e-books, every word is already indexed. We’ll still need a copyright notice, but I’ve seen texts now that just have a link to a rights notice on a server somewhere. It’s like an abstraction of an abstraction.

E-books will continue to have “covers” although it’s impossible to say what’s being covered. Indexing will die off, since in e-books, every word is already indexed. We’ll still need a copyright notice, but I’ve seen texts now that just have a link to a rights notice on a server somewhere. It’s like an abstraction of an abstraction.

I don’t think the print book will disappear anytime soon, but there’s an exciting kind of terror to realize we are navigating the uncertain waters of epochal change. When I was growing up, hot metal type was the norm. It was dethroned by the allmighty offset press and photolithography. But in technology, you don’t get to dominate for long.

The more I think about it, the more I agree with the remark E.M. Ginger made at the recent BAIPA meeting: I’m not sure we’ve seen a digital “book” yet, and I’m not sure we ever will. Not even from Apple.

What do you think?