Monospace fonts hail back to the early days of the typewriter. Today, they’re primarily used to mimic a typewriter effect, or when writing code (there are some other fringe use cases, too).

Okay, I’m going to come clean and admit that I learned to type on a big, hulking pile of metal call a Remington typewriter. The keys on the typewriters in our 9th grade classroom had been covered with blank key caps. We were learning touch typing.

It was actually hard to learn how to strike the keys hard enough to send the metal levers toward the paper with enough impact to make a legible impression. Very physical. I’m still relearning how to type on electronic keyboards, and have to stop myself when I get excited from banging away like I was back at the old Remington.

With the invention of the typewriter came the need for type fonts designed for this new technology. The fonts that were introduced for the typewriter, and that we still think of as “typewriter fonts” are basically slab serif fonts. But there was a crucial difference to these fonts: every letter takes up the same amount of space on the line.

Since they use only one set width for all the letters, numbers and punctuation, these fonts have come to be called monospaced. Most type fonts are proportionally spaced meaning that the letters have different proportional widths depending on their design. So, for instance, an “i” in Times Roman or Garamond or Helvetica—all proportionally spaced fonts—is much narrower than an “m”.

But in a monospace font, they are all the same.

This gives monospace fonts a particular character. They were the mainstays not only of typewriters, which could only move one space at a time, but also early CRT screens, where characters were made from pixels in boxes that were all the same size.

In covering monospace fonts, we’ll discuss:

The Monospace Fonts Live On

Rather than being left behind by the mathematical power of the computer, which makes spacing proportional fonts quite easy, monospace fonts have continued to be popular for lots of reasons.

The one I’m writing about today though, is very personal. Let me tell you why.

Once the desktop publishing revolution took over with the introduction of the first Macs and Pagemaker software, proportional fonts became the rule. Where everything had been typewritten or printed on dot matrix printers—more monospace fonts—now people were writing books, letters, and memos in Palatino, Times Roman, and lots of other real typefaces.

I was writing a book at the time and also doing a lot of editing. I had trouble for some reason concentrating on the manuscripts I would print out for marking up. There was something wrong, and I couldn’t put my finger on it.

So I started to experiment with typefaces, line spacing and anything else I could think of. One day I realized that I never had these problems with manuscripts that were submitted as a stack of typewritten sheets. I took the document I was working on and, after a moment’s hesitation, threw out all the lovely proportional typography. Instead I set the whole thing in Courier, the monospace font that’s found on every computer.

After fooling around with the settings for a bit I found one that looked quite a bit like typescript. I was a happy editor.

What Is It About Monospace Fonts?

There’s a bit of magic for me in these monospace fonts. When I started editing on my new imitation typewriter printout, the font itself seemed to disappear. Like typescript, it was so pedestrian it simply vanished, leaving only the content.

Since then—and despite being a professional typographer—I’ve preferred monospace fonts for creative work. They allow me to write and edit with no distraction from typography. You know, most typefaces used in books look plain in a big gray mass of type on a page. But up close they are full of rhythm, eccentricity, odd details and angles that go in every direction.

Monospace fonts, by contrast, are usually very plain, with consistent stroke weights and open, readable letters.

Variations on the Monospace Font

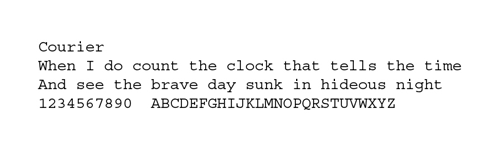

Here’s Courier, still the standard for monospace fonts on computers:

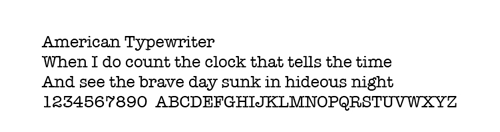

These fonts have also inspired type designers to adapt them in lots of interesting ways. Here’s a classic, American Typewriter:

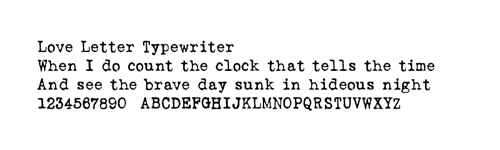

Even the grunge font fad has caught up with these fonts. Here’s one of my favorites, Love Letter Typewriter:

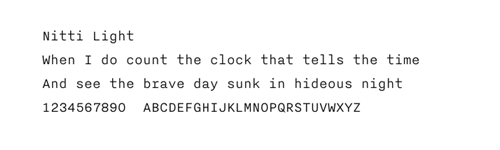

Finally, the font that I spend the most time with these days, Nitti Light, exclusive to the iPad writing app iA Writer. Here’s what iA says about it:

Writer uses a monospace font called Nitti Light created and optimized for iPad by the type wizards at Bold Monday. The font transports the provisory character of drafting and forces you to read slowly and precisely without being tedious to look at.

I’ve been doing this so long that I unconsciously associate monospace fonts with creative work of some kind. One of the things that attracted me to Writer for the iPad was the clean display and unadorned typeface. The combination creates a kind of white noise of the mind, a space within which it’s possible to think and transcribe creative thoughts in an almost frictionless environment.

I don’t know if you’ll get what I mean here, but try using a monospace font as an experiment when you have some creative work to do. Don’t attempt to format and write at the same time. Set up a plain page in Courier or some other monospace font and just write like there’s nothing else in the world but you and that screen in front of you. Without encumbrance or distraction, let it flow.

Photo by MPClemens