Although the vast majority of print books published by indie authors are print on demand paperbacks, there are lots of other kinds of books we can publish.

Sometimes a different format or a book with more features to it can really help you stand out in the crowd and create desire for your book.

Recently I’ve helped produce a number of workbooks for a variety of clients, and I’m working one right now. When authors ask me the best way to produce these books, and if they can be done through the usual print on demand vendors, we often get into a prolonged discussion.

That’s because although print on demand is a terrific innovation that eliminates the financial risk in print book publishing, it has severe limitations, too.

But sometimes the standard print on demand paperback just won’t do.

For instance, suppose you are publishing a workbook. This is a great way to extend a franchise created by an instructional or inspirational book, and allows you to quickly create another book that will please your readers.

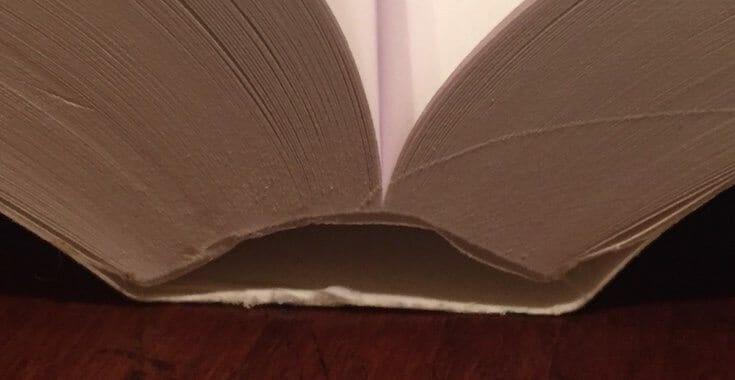

But a typical print on demand paperback has a pretty stiff spine, and most of them do not open all the way so they can lay flat on your desk. That’s what you want if you intend that your readers write in them.

Whether you’re teaching a process or preparing people to take a standardized exam, or providing ways for individuals to apply the ideas in a book you’ve published, workbooks are popular with both readers and publishers.

But a book that won’t lay flat when you want to write in it can be a pain.

Journals, Cookbooks, and Manuals, Too

When you start thinking about it, there are lots of books that would benefit from a binding that allows the book to be opened fully and laid flat when necessary.

But how to do it?

That’s the question I faced when I started putting together the requirements for my WriteWell Writers Journals (currently in production).

One of the reasons I dislike hardcover journals is that most of them are also made with tight spines that don’t allow the book to lay flat.

But there are other kinds of books that can benefit from a lay flat spine.

- Journals, diaries, daily quote books with lines to record your own thoughts, all these books would benefit from a binding intended to help people use them as they were meant to be used.

- Cookbooks repay the investment in better binding because you make your book easier for cooks to use in the kitchen.

- Manuals that you need to refer to while doing a repair or other operation are much more useful if they lay flat next to you.

I bet you can think of your own examples, too.

During my research I looked at a lot of binding styles, each of which can create a lay flat binding or something very close. I also learned a lot about adhesives and binding techniques.

Here are some of the methods and processes that I ran across:

- Spiral/Wire-O/Comb bindings—These binding can be grouped together since they all involve punching holes in the sheets of paper that make up the book, then insert wire or plastic to bind the pages. Although these bindings do lay flat, they present other problems. The wires can bend, the plastic “fingers” can come loose, they are awkward to pack, and many bookstores don’t like them because they are hard to shelve. Aesthetically, they leave a lot to be desired for trade books.

- Sewn bindings—You might be surprised that binding books by sewing the signatures together and them affixing them to a cover is still being used. After all, it’s the oldest style of binding there is. and that’s exactly how the Gutenberg Bible was bound. With today’s Smyth sewing machines, trade books can be economically sewn together providing the strongest binding, and the one with the most integrity to the way the book was manufactured. This is the method I chose in the end to use on the WriteWell journals.

- Otabind/RepKover—Two variations on a proprietary system that allows the spine to flex separately from the cover, allowing a great degree of flexibility and the ability to lay quite flat. Unfortunately, this technology is most appropriate for long runs of books, or titles with a high cover price because the manufacturing will add substantially to the cost of the books to the publisher.

RepKover binding, clearly showing the spine flexing independent of the cover. (Courtesy Edwards Brothers Malloy)

- PUR vs EVA adhesives—Until the 1990s perfect bound paperbacks used EVA (Ethylene Vinyl Acetate) glue almost exclusively. You may recall early versions of this adhesive for its ability to dry out, crack, and start shedding pages. But it got better with time, until the appearance of PUR (Polyurethane Reactive) adhesive. Using completely different chemistry, PUR is able to create a permanent, flexible, strong binding with less material than EVA. Because it requires more curing time, some printers have been reluctant to embrace it, but I’ve seen PUR-bound books that were astonishing because I could turn them as open as a book can be, and the individual pages simply would not budge.

My conclusion, after quite a bit of research, testing, having prototype books created so I could try to destroy them, is this: sewn bindings will give your book a structural and aesthetic integrity unachievable by other means, and it’s surprisingly affordable from the right vendors. And PUR is the undisputed choice for books that need a flexible binding and permanent adhesion, so it pays to check with your print vendor.

Resources

- The Book Designer, Self-Publishing Basics: 5 Book Binding Styles Illustrated

- Thomson-Shore, Bind Styles Reference (Illustrated PDF download, an excellent reference point)

- Hyphen Press, Books That Lie Open

- Make Your Book Real, Bookbinding: Otabind

- Edwards Brothers Malloy, RepKover (PDF)

- Trade Bindery Service, PUR Binding vs. EVA Binding – Why It Matters

- Duplo International, Why PUR adhesive is better than EVA adhesive for book binding