By Florence Osmund

I recently had the opportunity to evaluate Marlowe, Authors A.I.’s analytical software for novels. Created by Matthew L. Jockers, Ph.D., and his data team, Marlowe is an artificial intelligence that serves to help authors improve their novel before sending it off for professional editing. The goal of this software is to “help authors refine their manuscripts and identify new market opportunities for their works.” (Note: I searched their website but did not find any reference to helping authors “identify new market opportunities for their works.”)

Marlowe is relatively new—first released in January 2020—and so I was a little skeptical about the reliability of the algorithms, fearing its creators could still be working out the kinks. Also new is the Authors A.I. organization itself, a June 2019 venture.

The manuscript I submitted to Marlowe was the final manuscript for my latest novel Nineteen Hundred Days, a book in the literary fiction genre that had gone through three levels of professional editing:

- manuscript critique

- line editing

- copy editing

The 24-page report I received for this manuscript includes 15 areas of analyses.

Plot Structure

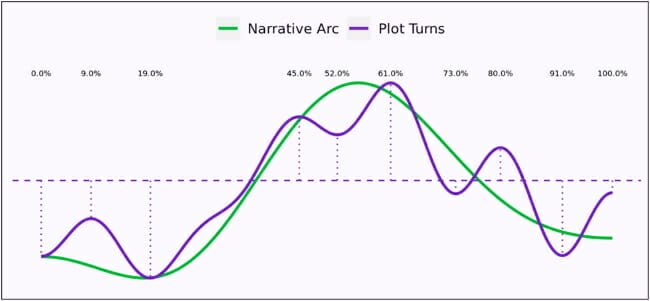

This section of the Marlowe report is about narrative arc and major turning points in the story line. Below is the visual representation provided for my novel.

The dotted line running across the graph indicates emotional neutrality.

The purple line represents conflict and conflict resolution. Upward slopes mark instances of conflict resolution where the story takes a positive turn, and downward slopes indicate the story taking a darker turn or some level of complication.

The more peaks and valleys, the more of an emotional roller coaster the character(s) is going on, which could be an indication of how successful the novel is in engaging readers. If the purple line doesn’t veer away much from the dotted line, the story is likely flat and uninteresting.

According to Marlowe, a good story will result in this line vacillating between above and below the dotted line with highs and lows throughout. And it’s not just about the number of spikes, it’s also about the depth of each one.

The green line represents the narrative arc. Marlowe claims there is no optimal shape for the narrative arc, and they are working on obtaining some comps from bestsellers for future reference. But my experience is that fictional stories are best structured if they include these narrative arc components:

- exposition

- conflict

- rising action

- climax

- falling action

- resolution

When optimally included in the story line, these components form a definitive narrative arc.

My interpretation of this analysis for Nineteen Hundred Days is that it has a typical narrative arc (at least according to my knowledge and experience). With respect to the level and depth of conflict in the story line, I can only compare it to the sample report that Authors A. I. has on its website for The Da Vinci Code which has five peaks (compared to my six) with approximately the same depth and occurrences above and below the dotted line. While my novel is not in the same league as The Da Vinci Code, I can only feel good about this comparison.

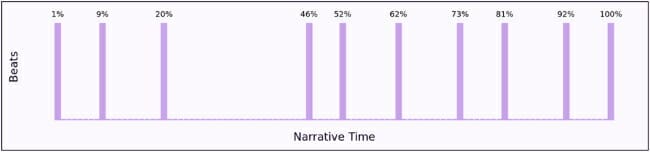

Narrative Beats

Marlowe defines narrative beats as the turning points of the story, occurring where new conflict is introduced or when conflict is resolved. They cite best-selling novels The Da Vinci Code and Fifty Shades of Grey as having beats evenly spaced throughout the narrative at approximately 10% intervals.

Here is the graph for my novel:

My interpretation of this analysis for my novel is that, except for a lull in conflict approximately 30% into the book, the narrative beats are in synch with what Marlowe believes to be on par with at least two bestsellers. Regarding the lull between 20% and 46%, that would be between chapters eight and eighteen in my book. There is plenty of conflict in these chapters, so I must question Marlowe’s analysis.

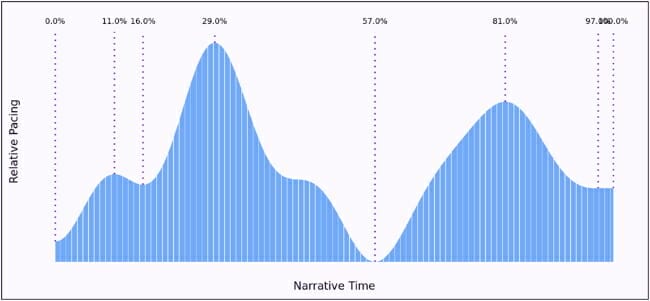

Pacing

Marlowe analyzes the story’s pacing by plotting where it thinks readers will turn the pages more quickly (peaks on the graph) and the slower moments (valleys) where there is likely scene setting and background information given, claiming that the most successful writers vary the pace of their story to provide variety.

When I saw this analysis for my novel, I immediately wondered what was going on at the 57% mark to cause such a prominent “valley.” So I looked at chapters 20 through 25 and found three significant events:

- the protagonist’s best friend dies of cancer

- he is asked by police if he can identify someone they are looking for

- he learns of his mother’s jail sentence

I would not call these “slow moments,” so I am at a loss as to why the graph dips so low at the 57% mark.

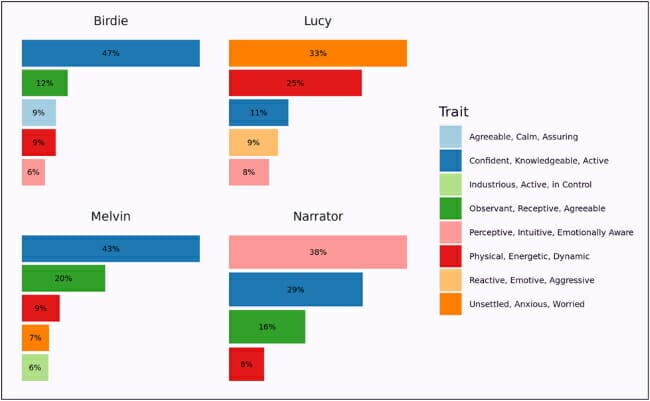

Characters’ Personality Traits

This is an area that Marlowe’s creators admit is still a work in progress—evaluating the characters’ personality traits based on their actions. Considering their analysis of my characters, I agree they need to work on this. But one thing I believe is worth looking at is whether your protagonist is too reactive or the antagonist too agreeable—both scenarios being problematic for good storytelling.

Since my novel is written in first person, the narrator is also the protagonist, and his name is Ben. I would agree that Ben’s most significant trait is being perceptive, intuitive, and emotionally aware. After all, at twelve, he figures out how to save himself and his sister Lucy from being discovered by Social Services, and that includes his driving a car to his Aunt Birdie’s house. Why unsettled, anxious, and worried did not make the list for Ben is questionable.

Lucy is indeed mostly unsettled, anxious, and worried, but she is not physical, energetic, or dynamic, nor is she confident, knowledgeable, and active. She is reactive, but not aggressive.

I do not think Marlowe hit the mark on Aunt Birdie either. She saves the day for Ben, and I believe her strongest trait is agreeable, calm, and assuring followed by perceptive, intuitive, and emotionally aware. I do not see her as particularly confident, knowledgeable, and active.

Melvin is a lost soul in the story. He drinks too much, has a past police record, is scary to little children, and has bad manners. But he is also the one who befriends Ben and is there for him in the end. Given the way the traits are grouped in this analysis, the ones Marlowe picked for Melvin are not too far off.

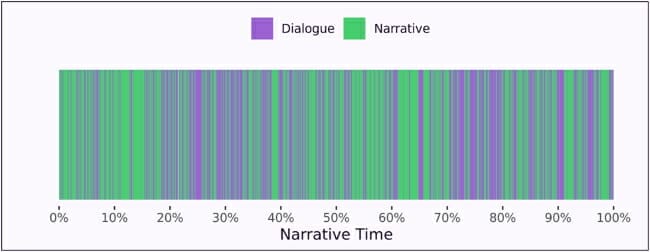

Dialogue vs. Narrative

Marlowe claims that most popular novels contain between 25% and 35% dialogue. They also recommend that dialogue is evenly spaced throughout the manuscript.

My manuscript contains 41% dialogue, slightly more than what they recommend. The dialogue appears to be evenly spaced throughout the novel.

It would have been helpful to include the percentage of internal dialogue in the manuscript. Too much and the story is probably lacking action. Too little and readers may be wondering what is going through the character’s mind.

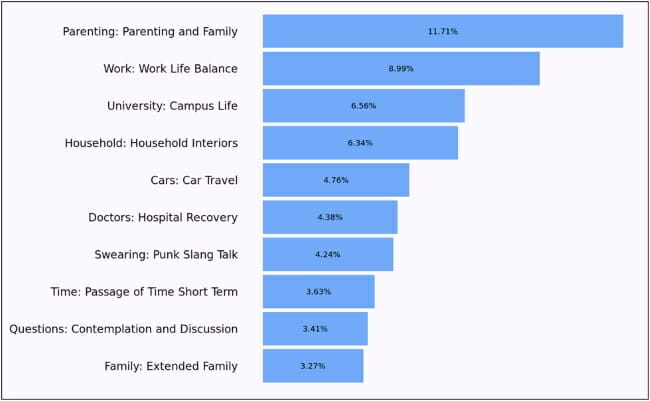

Major Story Subjects

This section of the analysis identifies ten primary topics in the narrative and estimates the percentage of text devoted to each one. Marlowe’s research has found that successful novels typically have one or two primary topics and one or two secondary topics that when combined account for approximately 30% of the overall topical makeup of the book. They claim, “Telling the heart of a story with fewer topics implies focus [and] a more organized and precise writerly mind.”

I would not have chosen these ten topics for my book. For example, I am not sure how Work: Work Life Balance and University: Campus Life even made the list. And Family: Extended Family belongs high up on the list as opposed to the very bottom where they have placed it. It is not clear to me what Questions: Contemplation and Discussion and Time: Passage of Time Short Term are. Definitions of these terms would have been helpful.

Explicit Language

To identify words that readers could find offensive, Marlowe flagged 18 of them in my manuscript. Some of the words flagged were tame, like ‘butt’ and ‘damn.’ One word the software flagged ten times was a character’s name (Dick), but I counted twenty-three times it had been used, not ten.

This is a helpful list, especially for authors concerned about including words in a book intended for a younger audience.

Clichés

Marlowe listed 22 clichés I used for a total of 30 occurrences. If that were true, shame on me, as clichés are generally overused and lack originality. But after searching for the ones listed in the report, I found they are either in someone’s dialogue, internal dialogue of an adolescent, or perfectly acceptable given the context of the sentence.

For example, these are three of the sentences that include what Marlowe flagged for the cliché ‘hands on.’

She stood facing him with her feet wide apart, hands on hips.

She walked toward me as she dried her hands on a dish towel.

She put both hands on her hips. “You mean you’d pick work and basketball over me?”

Even though the list includes phrases that are not actually used as a cliché, it is still a good list to have, as it reminds us that clichés are an indication of inferior writing.

Repetitive Phrases

Marlowe identified 27 repetitive phrases, each of which I used from 11 to 31 times in the manuscript. Some of them, like the ones listed below, are to be expected since the story is told in first person.

I had to

I didn’t know

I wanted to

I didn’t have

I have to

Lucy and I

When I was

For me to

Others may have been used repeatedly, but given the story line, they are not bothersome to me.

Mom and Dad

The living room

The ones that got my attention—ones I should have used less often—are these:

It was a

A lot of

To make sure

A couple of

This is a helpful list to have as we often do not realize we are using repetitive phrases unless someone points them out to us. I can remember my editor saying about one of my earlier books that my main character sighed way too often. I had not realized it and promptly fixed the problem.

Sentence Stats and Readability Score

Marlowe’s analysis included the following statistics on my manuscript.

It contains 6,824 sentences and 63,592 words.

The average length of a sentence is 10.15 words.

When I do the math, I get 9.32 for the average sentence length, so I am not sure how Marlowe is arriving at this statistic.

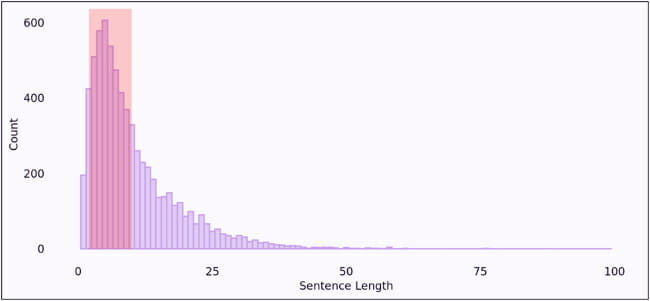

The Marlowe team’s research revealed that sentence lengths of successful novels range between two and ten words, so they suggest that the bulk of the sentences fall into this range. Here is a graphic illustration for my manuscript. The pink highlight indicates the two- to ten-word range.

Marlowe also measures the complexity and readability of the narrative by analyzing the syntax and grammar.

My manuscript scored an average readability suitable for those with a reading grade level of 4.49 and higher. My target audience is adult, but the book would also be suitable for teens.

The report doesn’t include any interpretation of this statistic, but according to the Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease scoring system, Ernest Hemmingway wrote at the fourth grade level; Cormac McCarthy, Suzanne Collins, and Jane Austin at the fifth grade level; and Danielle Steel, James Patterson, and John Grisham at an eighth grade level. I am still not sure how to interpret this for my book.

The report also states that books in the popular fiction market have sentences with a complexity score between 2.0 and 3.0. Sentences in my manuscript averaged 2.49 which puts it right in the middle.

Use of Adverbs

We all know that adverbs can be problematic in writing, and so I was glad to see the use of adverbs included in the analysis.

Marlow counted 288 adverbs ending in ‘ly’ in my manuscript. At first, I was horrified to read this because I check for these during my self-editing process. But when I searched the manuscript for the most frequently used adverb “really,” I discovered that the count includes adverbs used in dialogue. Dialogue, of course, is crafted according to each character’s personality (not what is necessarily grammatically correct or the best word usage).

Including adverbs in dialogue in my novel, where the protagonist is an adolescent, is misleading—35 of the 50 instances of “really” were in dialogue. The remaining fifteen were associated with the protagonist’s internal thoughts, so I do not consider any of these to be problematic.

Novels written in third person, and where the POV character is an adult, would likely benefit more from this analysis than mine did, as the overuse of adverbs can be more troublesome there.

Use of Adjectives

The report listed twenty adjectives that were used from 32 to 105 times in the manuscript. As with adverb usage, the analysis of adjective usage is not very helpful for my manuscript since some of the adjectives are included in dialogue strings, and the rest are associated with the young protagonist’s internal thoughts—all legitimate usage.

As with adverbs, I could see this analysis as being helpful in books written in third person. That said, I would liked to have seen a separate count for adjectives (and adverbs) that are contained within dialogue, as they may be less problematic.

Verb Choice and Passive Voice

We know that sentences written in active voice typically work better than those written in passive voice, and that is what Marlowe is trying to analyze in this section. While this analysis doesn’t work as well with first person POV as it would with third person, it is still somewhat helpful.

For example, the report shows 909 instances of my using the word “was.” Almost all these uses are associated with the protagonist’s internal thoughts. Still, many of these sentences could have been reworded to make them more active than passive.

Here is one example where twelve-year-old Ben is telling readers what he had scrounged up for lunch for himself and his sister.

Current sentence: The best I could do was toast with peanut butter, which was pretty hard to swallow without milk.

Better: I made us toast with peanut butter, a combination that proved hard to swallow without milk.

Again, this analysis would be more effective where the protagonist is an adult, and with third person narrative where there is less internalization.

Punctuation

The Marlowe report lists the following punctuation marks found in my manuscript:

| period | 5,247 |

| comma | 3,175 |

| opening quote | 2,780 |

| closing quote | 2,778 |

| question mark | 1,075 |

| em dash | 415 |

| hyphen | 295 |

| asterisk | 201 |

| ellipsis | 93 |

| exclamation point | 80 |

| apostrophe | 38 |

| colon | 12 |

| semi-colon | 8 |

| en dash | 1 |

| ellipsis | 1 |

| open parenthesis | 1 |

| closed parenthesis | 1 |

So, what does this tell me? Well, right off, I’m wondering why I have two more opening quotation marks than I have closing quotation marks. I do not have any dialogue spilling into the next paragraph, which would be one explanation. My Word software counted 5,559 quotation marks in my manuscript (it doesn’t distinguish between opening and closing marks) compared to Marlowe’s 5,558. So to start with, the two programs do not agree on the count.

I manually went through the document to see if I could find the quotation mark discrepancies—an arduous task to be sure. I found two instances where I was missing an opening quotation mark and one instance of a missing closing mark (how embarrassing). But Marlowe found two more opening quotation marks than closing marks, so something doesn’t jive. It would have been helpful if Marlowe had indicated where the missing marks occurred.

I use a series of three asterisks to separate major sections within a chapter, so it is good to know the number of asterisks that Marlowe found is divisible by three.

The report states that characters in bestsellers ask more questions than those not on the list. This is an interesting theory, but until Marlowe provides examples for comparison (which they are working on), I am not sure how my 1,075 question marks measure up.

The report also states that bestsellers use fewer exclamation points, colons, and semicolons. My manuscript contains:

- 80 exclamation points

- 12 colons

- 8 semicolons

When I went back to check out where I had used them, I found that the exclamation points are in dialogue; the colons are used when showing the time of day and listing one of the many rules the protagonist had to follow (Rule 1: Make your bed each morning), and six of the eight semicolons I used are in one sentence that lists a series of items the protagonist had found hidden in his parents’ home.

I tend to use a lot of em dashes in my writing, and Marlowe found 415 of them. Is this too many? I do not know. The report does not address this.

Possible Misspellings

Marlowe flagged 60 words that could be misspellings. Most of them are legitimate—words like blankie, podunk, snigger, and yawped. But four of them I was not certain of, so I checked them out.

drivable – According to Merriam-Webster, this is correct.

hol – This word was written by a five-year-old for the word ‘whole’.

figural – According to Merriam-Webster, this is correct.

th – I could not find this occurrence in the manuscript.

But the report did not include these possible misspellings that were spoken by an inebriated character:

schmolarship

Whusat

The above words are capitalized in the manuscript since they are the first words in the sentences, so I wonder if Marlowe assumed they were proper nouns and ignored them. Just a guess.

This report would be more useful if it included all the possible misspellings (including capitalized words) in that spell-checking software we authors use does not always catch everything.

In Conclusion

My manuscript for Nineteen Hundred Days came back relatively clean according to Marlowe, which is what I would expect for one that had been professionally edited. And I do not mind that in several of the analyses, they reported “possible” problems that I had to investigate to determine their validity. I would rather see too many potential problem areas listed that need investigation than to overlook some areas.

The real benefit of this software would obviously be when using it for early drafts, and especially for new authors who may not be as familiar with how to improve a manuscript so it is in better shape for an editor and/or more marketable.

According to their website, Authors A. I. offers three pricing plans:

| Free | Basic report (best for first-time authors) |

| $89 | One-time Pro analysis (the one I used) |

| $199/yr | Up to two Pro analyses per month plus some promotional opportunities |

If you are wondering where Marlowe got its name, it is from both:

- Christopher Marlowe, the Elizabethan tragedian who inspired Shakespeare

- Philip Marlowe, Raymond Chandler’s hardboiled private eye who plays chess and reads poetry

The founders like to think the software has Philip Marlowe’s intellect and investigative skills and Christopher Marlowe’s pioneering spirit and love for the written word.

Do I think Marlowe measures up to its namesakes? I think it definitely has potential once its creators work out what I found to be possible bugs, make it easier to locate the potential problem areas in the manuscript, and provide more comparable test results so we authors have something to which we can compare our manuscripts.

If anyone else has had experience with Marlowe, I would love to hear about it.

Want to read more articles by Florence Osmund? Click here.

Photo: BigStockPhoto. Amazon links contain affiliate code.