This article series continues in Part 2 and Part 3, make sure to read them all.

Suppose you’re an expert on something, anything really. You could be an expert on baking bread, on interior design, or on dog training.

You have specific skills and the experience of years of using your expertise in the real world, where it’s easy to measure results.

With all the attention around self-publishing in recent years, it’s quite likely that at some point you might start to think about writing down what you know, publishing a book on the subject.

If you come across advice from experts in self-publishing, you might also come to the realization that, in the right circumstances, you could make your book much more profitable by publishing it yourself.

Let’s suppose further that you’re actually a pretty good writer, with the ability explain things in a straightforward, conversational, engaging style. People like your stuff, and respond well to articles you’ve publishing in the past.

You might even have a blog or website that helps support your own career, or gathers some of your informational writings together for people who are interested.

But there’s only one problem.

The Problem With Book Publishing

The problem has to do with the long and costly development of most books. Unlike some fiction authors who seem to be able to turn out a new book every couple of months, instruction, how-to, and similar books can take a long time to develop and bring to market.

The distance between the moment when you have the thought, “Hey, if I write a book about baking bread/interior design/dog training, lots of people will want it!” and when you actually deposit the first check from your book sales, can be very long and expensive.

Just think of some of the tasks you’ll be facing:

- Outlining your book, deciding exactly what you’ll cover and how to make it useful

- Researching similar books to see if your concept makes sense or needs adjustment

- Writing the book

- Consulting with editors about changes that will make the book better and/or more salable

- Rewriting based on feedback from those editors

- Getting peer review and testimonials from others in your field

- Devising a marketing plan for the book, and planning a book launch

- Dealing with the physical and/or digital production of your book

- Making arrangements for distribution of your physical and digital books

- And, of course, paying up front for all this work by you and others

Just how long is it going to be before you see any payback on your efforts? And how long before you can say with any certainty at all whether the book is a “success” at accomplishing the goals you set out way back at the beginning, when you first decided to publish?

And the more complex your expertise, the deeper the field in which you practice, the more time and energy it’s likely to take to get all this done and put together in a way that will actually be useful to your prospective reader.

It’s enough to make you pause, yes?

But maybe there’s another way.

Turning Things Sideways

An alternative to the process I outlined above comes right out of the book itself: the table of contents.

Think about a typical contents page in an instructional book. Your chapters might look something like this, and here I’ll use the example of pizza baking:

- An Introduction to Pizza

History and general context for the study of pizza baking - Tools and Equipment

Essential tools and shopping suggestions to stock your kitchen for pizza baking - Mysteries of Yeast

How to deal with this intrinsic ingredient for taste and texture - A Simple Pizza Dough

Making your first batch of pizza dough, step by step directions - Going Beyond the Basic Dough Recipe

Instructions for pizza dough recipes borrowing from many cultures - The Wonderful Word of Toppings

How to plan, prepare, and use topping ingedients - It’s All In the Wrist

Specific skills you’ll need to learn to be successful - Going Beyond the Basics

Specialty pizzas, flatbreads, and other ways to use your new skills

This is a simplified plan, but it shows how you might go about teaching pizza baking in a book that would actually help readers.

But look at the chapter titles again for a second. There’s something else lurking behind the way this list is presented: chronology.

Many books of instruction contain an implied chronology to their contents. What I mean is that you really do have to start at the beginning. Each chapter contains information you’ll need to learn before you move on to the next.

Each chapter subject builds on the lessons that came before. I can’t teach you how to flip the dough onto the pizza stone if you don’t know about dough, pizza peels (the thing you carry the dough on) and pizza stones.

Likewise, you can’t learn about toppings until you know the different kinds of crusts you can make.

As in many fields, you start with the basics and build proficiency one step at a time. And that’s where the “sideways” part comes in.

Going Sideways

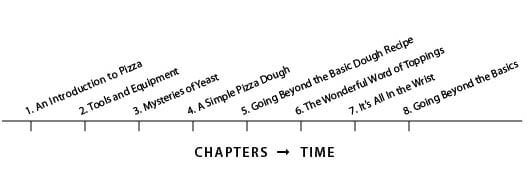

Here’s what our contents might look like if we expressed this chronology in a timeline instead of a list of chapters:

This makes it abundantly clear that chapter one must come before chapter two, enforced by the strictures of time passing from left to right. After you’ve learned the background, we’ll move on to getting the right tools and supplies. You just have to do it in order.

Exactly how this plays out, and the implications for authors of instructional or how-to books, will be subject of part 2, so check back on Wednesday and you’ll see exactly where I’m going with this idea.

I promise it can change the way you look at these book projects forever.

Photo by photo credit: boltron- via photopin cc. (Ed: I’ve borrowed significant concepts for this idea from internet marketing guru Jeff Walker, where he applied it to an online sales process.)