I’ve been thinking about keyboards lately, you’ll see why in a minute.

The keyboard is a pretty amazing thing. Invented in the late 19th century along with the mechanism to imprint “type-writing” onto paper, keyboards first appeared as the operational end of the typewriter.

Up until that time, all writing by all writers, authors, novelists, historians, speechwriters—every one of them—was written by hand.

So the appearance of the typewriter signaled a true communications revolution. Soon typewriters were in use in business, academia, and were the very symbol of the new age of mechanical efficiency.

And there is something exciting about learning your way around a keyboard for the first time. Until then, watching someone else type is like watching a skilled musician coax beautiful music from a collection of metal, wood, plastic, and bone. Words appear, flowing across the paper—or the screen these days—making arguments, entertainments, or simply shopping lists.

Because I’m older than you are, I learned to type on a manual typewriter in typing class in high school. The keys had no letters on them, they had been covered up because it was a “touch typing” class.

Virtually the entire class consisted of us practicing repetitive letter combinations on the massive Royal and Remington typewriters bolted to the wooden desks in the typing room. It was pretty noisy.

There’s a lot of history and lore to the invention of the typewriter, as well as lots of arguments for and against the “QUERTY” keyboard arrangement we’ve all had to learn.

But that’s not my interest today.

A Personal History of the Modern Keyboard

No, what interests me as a writer is the keyboard as a tool to move my thoughts from my head onto paper (in the case of typewriting) or even more remarkable, move them from the physical world into the digital world.

Because that’s what we do with our keyboards.

No one has yet devised a more efficient way for us to transfer our thinking to the digital realm, where it can be edited, manipulated, re-arranged, and analyzed in many ways.

That day will surely come, but until then writers everywhere will rely on their keyboards as the most used piece of equipment in ours arsenal, the one that we are physically in contact with most of all.

This past week I acquired a new computer, and with it came a new keyboard, the latest in a very long line of keyboards that have responded, for better or worse, to my banging on them.

Here’s a brief overview of my own history with these pedestrian objects. I’ve got boxes full of keyboards in my garage, and I hardly notice the ones I use. Yet they have carried the over-1-million words I’ve written on this blog. They allow me to send my (formatted and edited) thoughts to you, no matter where you are in the world.

Although I’ve got a lot of keyboards to show you below, there are so many more that exist only in my memory. I’ve worked on Wang word processors, the original Apple II, and so many others it’s hard to remember. I bet you have a history all your own with keyboards.

Here’s a look at mine.

Keyboards of My Life

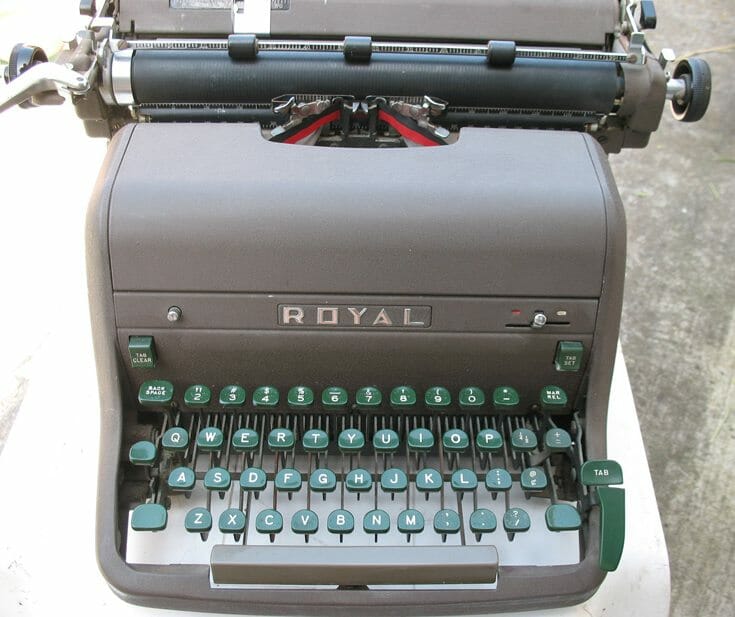

Royal Typewriter

This is very similar to the typewriters I learned to type on, with one big exception: it has letters on the keycaps. In typing class, these were covered so you were forced, from day 1, to “touch type” and a good deal of the entire course was spent on repetitive drills to teach us the keyboard. This is a substantial, heavy piece of machinery, and it took a lot of effort to hit the keys hard enough to make a clean impression. My career as a “banger” began.

Linotype keyboard

My dad worked on these more than I did, but they are interesting for a couple of reasons. The linotype was a machine that cast lead slugs of type, one line at a time. Because they had no “shift” function like we do on our keyboards, they had a separate keyboard for lower case, one for small caps, and one for capital letters. (Also note the “quadder” on the right for setting flush right, flush left, or centered copy.)

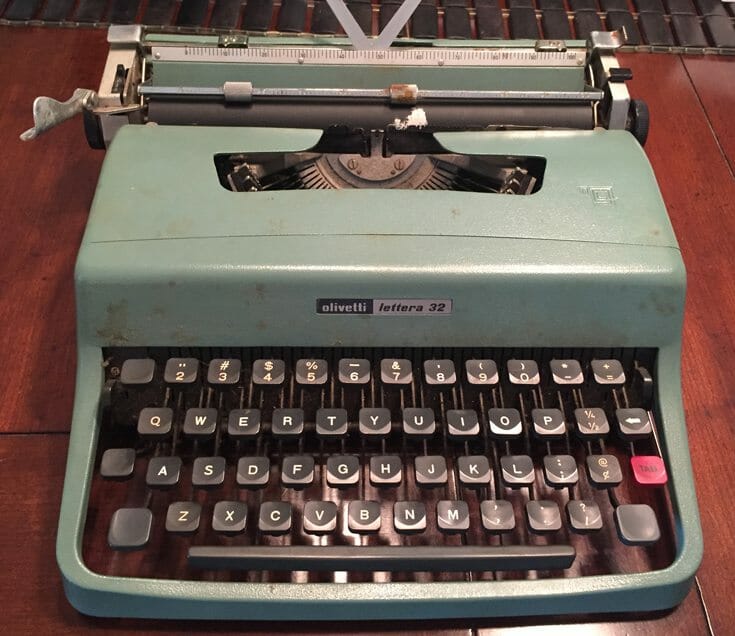

Olivetti Lettera

This is my favorite manual typewriter of all time. It was, in its day, the “laptop” version of a desk typewriter, and was used by many journalists and correspondents. It has a lovely zippered case, can take a beating, and is remarkably light. I wrote my first book on this exact machine, both the first and second drafts. Then I went and bought my first computer!

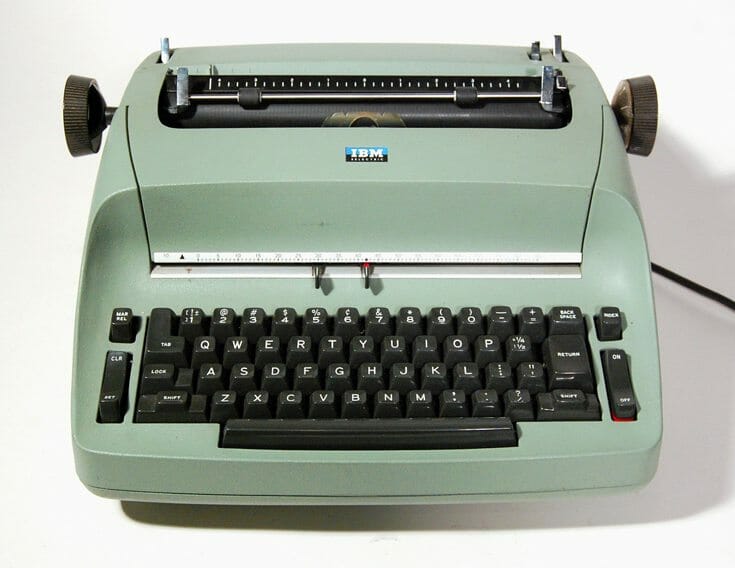

IBM Selectric Typewriter

Without a doubt, the ultimate typewriter, the apotheosis of what a typewriter could be. Gone are the awkward keys that always stuck and slowed you down, gone is the klunky design, gone is the carriage moving back and forth. To this day, I’ve never operated a machine that was smoother or more enjoyable to work on than this one, and I held onto one of these beauties until a few years ago. It eventually morphed into the IBM Selectric Composer, a real typesetter with a memory function, one of the first of its kind.

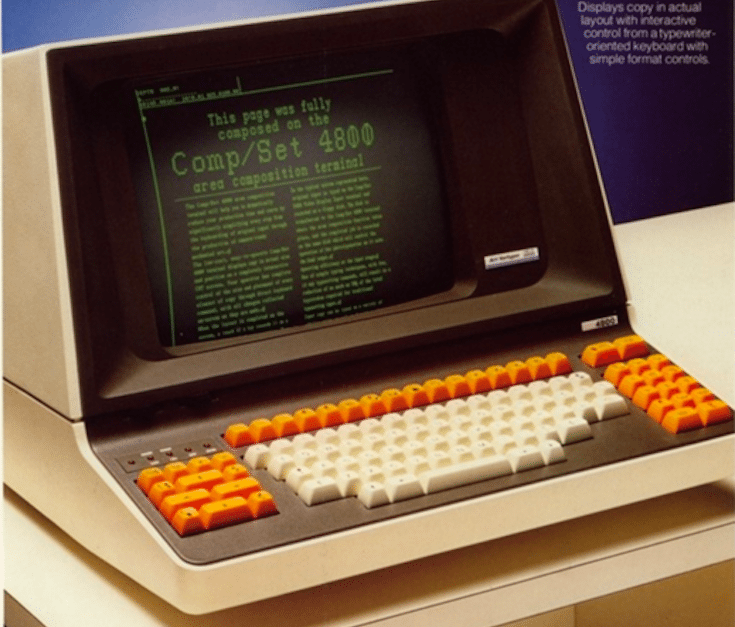

AM Comp Set

One of the first commercial phototypesetters, the 1980 AM Comp Set could keep over 2,200 fonts online and boasted a memory of 80 K (“more than double any competitive machine”). It ran with floppy drives and 8″ floppy disks–and they really flopped. I ran one of these at a large financial services company in New York, and it was the first time I experienced the connection between “coding” the material to be set, and the phototypesetter’s output of a graphic arts element. This connection of coding to art would blossom soon thereafter.

Linotype CRTronic

In a classic move of bad timing, I acquired one of these early desktop typesetting workstations and all the photo equipment necessary to do my own phototypesetting when I had a design business on Fifth Avenue in New York. Bad timing, because about a year later the IBM PC came out, rendering all of these $37,000 terminals lovely piles of obsolescence. But, you still had to pay for it—perfect!

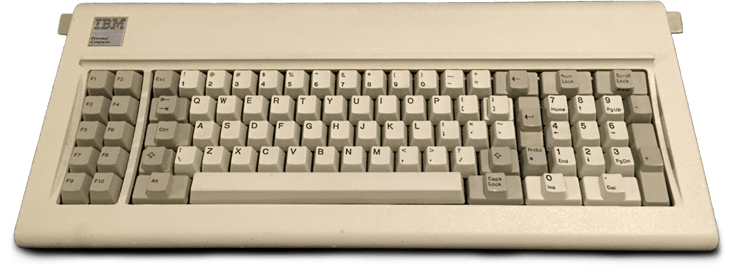

IBM Model F Keyboard

Later, its successor, the Model M would become one of the most popular and widely-used pieces of business equipment in the history of the world. But this was the original, the one that started the “computer revolution.” I spent many hours banging on these keyboards, and they are not like what you know today. They are mechanical with actual springs under each key that give a very crisp “click” when they break into action. The solid feel of the keyboard, the excellent materials, and the audible feedback combine in this keyboard to create a classic of the art. These keyboards are so revered, you can even buy one today, retrofitted for today’s USB connectors (see Resources at the end).

Apple Pro Keyboard

When I switched from IBM PCs to Apple Macintoshes, I got introduced to the Apple keyboards. This one was fairly comfortable, and with all the keys you could possibly want. The styling matched the clear cases of the Macs of that era.

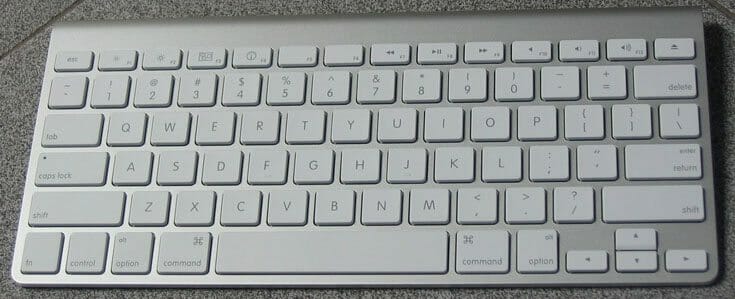

Apple Wireless Keyboard

I’ve probably typed more words on this keyboard than on any other. I used one for years with my iPad, then used them with my iMacs. It’s a small, lightweight, minimal but functional keyboard. These Apple keyboards don’t have a numeric keypad, which can be handy, but they are incredibly light to carry around. My only problem has been the huge number of AA batteries I’ve been going through the last few years. Both from an ecological and financial point of view, I needed a change.

Apple Magic Keyboard

And that brings us to today. With my new iMac, I decided to skip the wireless option, skip the dropped Bluetooth connections and low battery alerts and go retro with a wired keyboard and mouse. Boy, am I glad I did. This new (2015) Apple keyboard is the most minimal piece of equipment I own. It’s much slimmer than the wireless, since it needs no batteries.

The most minimalist keyboard I’ve ever used, it feels like a thin slab on your desk. It has a silky feel that’s delightful, and although I may be kidding myself, it feels appreciably faster than my old keyboard.

Stroking, Not Banging!

Here’s a story: A few years ago I headed down to the Apple store to complain about the Apple Wireless keyboard I was using at the time. I found an older woman who worked there and told her how the keyboard hurt my fingers, and did they have anything else?

She looked at me for a minute, then asked, “Did you learn to type on a manual?”

“Sure,” I said.

“That’s your problem,” she said. “You’re banging on the keys, because that’s what you learned on those big metal typewriters. These keyboards aren’t made to be banged on.”

“No?”

“No. Try tapping the keys. Even better, try stroking them. Don’t bang them and your fingers won’t hurt!”

And, of course, she was right. I’m trying, really I am. Although old habits die hard, I want you to know that my new Apple Magic keyboard really rewards stroking.

Writers should appreciate their keyboards. They are the workhorses that allow us to transmit our words and ideas. Here I sit in my office in San Rafael, tapping away these words for you.

Do you have a favorite keyboard? Tell me about it in the comments.

Credits and Resources

Buy a USB IBM Model M Keyboard

History of the IBM Model M Keyboard

Postscript: Some time after this post was written, I ended up buying two new keyboards. For the story, see: Writer’s Tools and the Forgotten Keyboard

IBM Selectric (green): Steve Lodefink https://www.flickr.com/photos/lodefink/4317923430

CRTronic: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a3/Linotype_CRTronic_360.jpg

Apple Pro Keyboard (black): CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16768

Apple wireless keyboard: By Roadmr – Own work, GFDL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3160133

Apple wireless keyboard (side view): By Roadmr – Own work, GFDL, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3160142