At this point we’ve all heard of ebooks, and most of us have probably read at least a few of them. But what is an ebook? Does a PDF count? Or is it only an ebook if it uses a specialized ebook format?

There are lots of very complex questions when it comes to ebooks:

- text and image formatting,

- different file formats,

- various workflows for creating ebooks,

- and much more.

In this article about what an ebook is, we’ll cover:

So What IS an Ebook?

For this post, before we get into the more esoteric issues of ebook design and publishing, I’d like to start by defining the subject: just what is an ebook?

This may sound like a very simple question to answer, but it isn’t as straightforward as you might think, and being able to answer it correctly will make many of the thornier issues of creating ebooks just a bit easier.

If I were to ask most folks to answer that question they’d probably say that an ebook is a digital file for reading text on a digital device—a computer, tablet, dedicated ebook reader, or smart phone. And that answer would be true, so far as it went.

Unfortunately, that definition would cover a wide variety of documents that aren’t ebooks. A Microsoft Word file, for example, is a great way to compose and share formatted text—heck, you can even add images and hyperlinks, just like an ebook.

Word docs, however, are by definition meant for writing and editing the text, not for distributing it commercially. We don’t want our readers rewriting sections of our books without our permission, do we? If they don’t like what we’ve written, fine; they can write their own books!

Characteristics of an eBook

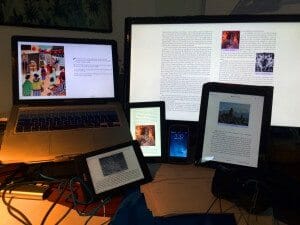

What a true ebook does is present correctly formatted text and images no matter the size of the screen it’s being displayed on. In order to do this, ebooks get rid of the idea of a page; the text will format to flow properly, and when one screen is full, will flow to the next—that is, they are reflowable. (This leads to some really fun exchanges between ebook designers and their clients. I love getting lists of notes from clients saying that a particular problem shows up on “page 23.” I have to point out to them that page 23 on their laptop may be page 12 on my big monitor or page 124 on my phone.)

Images in ebooks will resize (if the book has been properly designed) to the proportions of the screen. Ideally the book will be attractive and easy to read on any device—and because each software application for reading ebooks has some reader controls, some whose vision is no longer as strong as it once was (like, say, me) can make it larger, while someone who doesn’t like serif fonts can have the book display in sans-serif or, heck, Zapfino (don’t try this at home). And this can all be done without changing the ebook itself—the changes are simply user preferences within the app.

To give an idea of what I mean, here is a photo of the same book displayed on a number of different devices—just the ones that I happened to have on my desk:

Are PDFs Ebooks?

A kind of digital file that is frequently referred to as an ebook but that isn’t is the PDF—the now-universal Portable Digital File format that Adobe invented as a way of distributing print documents digitally. Not only is it how we share our own personal documents (letters, etc.) through the internet, but it’s how publishers have been transferring print-ready files to commercial printers for decades. How is that not an ebook, you ask?

The PDF isn’t truly an ebook because it retains its format no matter the size of the screen that displays it. It will always be an accurate representation of the paper document that it represents—on a 27″ monitor, on a 13″ laptop display, on an 9.7″ iPad screen, or a 4.8″ Galaxy s3 phone.

The basic unit for a PDF is the page. And so as the screen shrinks, so does the page size, and with it the size of the words, and with them the readability. Anyone who’s tried to read a PDF on a small screen knows what I mean.

The History of eBook Formats

Now, there’s another kind of file that is meant to do very much the same thing—and you’re looking at one right now. Web pages provide exactly the flexibility that ebooks require. And so when the International Digital Publishing Forum (IDPF) started looking at trying to create a new ebook standard over a decade ago, they looked to the language of the web—HTML—as a basic building block.

At the time, there were many competing “ebook” formats that publishers and distributors were trying to get tech companies to use:

- PDFs,

- Palm’s mobi or Mobipocket files (the database-driven basis for the original Kindle file format),

- Microsoft’s LIT (an HTML-based format, but proprietary, intended for books to be read on the Microsoft Reader app),

- and a few more.

The IDPF created a format that created a self-contained set of HTML files in a very specific format, and called it ePub. In the past decade, it has become the standard ebook file format. Most ebook reader apps and devices use some variation on the ePub file format to display text and images properly, including all of the Kindles that Amazon is currently shipping.

And the ePub file itself is nothing more than a self-contained package containing a group of HTML files, with its own set of styles for formatting and a navigation document (or two) for making sure everything gets displayed in the right order.

And that is what an ebook is: a website in a box.

Next time, I’ll talk about what that actually means and how to create your own ebooks.

David Kudler is a Contributing Writer for TheBookDesigner.com. He is also an author, an editor, an ebook designer and a writer for the Huffington Post.

You can learn more about David here.

Photo: bigstockphoto.com